Is there any proper theory behind war? I wouldn’t say so. Most of the time, it’s

just rage , the urge to fight and to win. If we look back at history, many wars

didn’t even have a valid reason. Maybe they gave a reason, but was it really

worth all the destruction?

Even when you have a quarrel with your neighbour, there could be a reason —

they encroached on your property, cut your trees, or something else. But when

two countries go to war, what reason justifies the massive loss of life and

resources?

Take World War I and World War II, for example.

World War I: The immediate cause was the assassination of Archduke Franz

Ferdinand of Austria-Hungary in 1914. However, underlying causes included

militarism, alliances, imperialism, and nationalism among European powers.

World War II: The immediate cause was Germany’s invasion of Poland in 1939.

Deeper causes included the harsh terms of the Treaty of Versailles, economic

instability from the Great Depression, and the rise of fascist regimes in

Germany, Italy, and Japan.

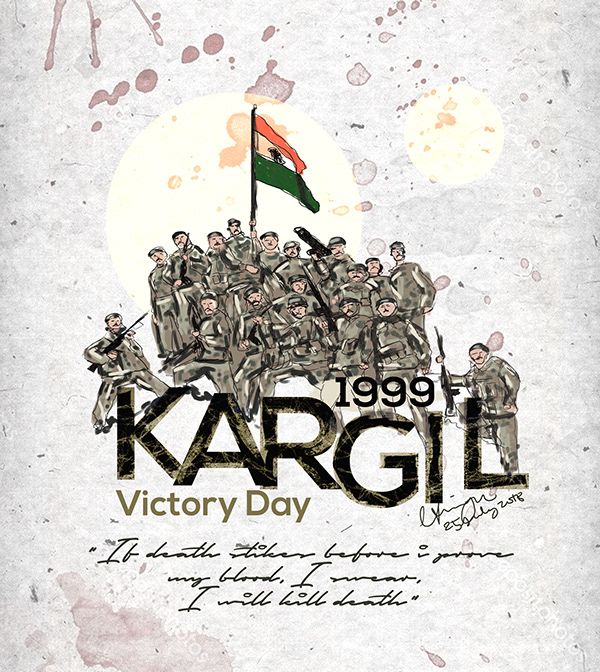

Now, consider the last India-Pakistan war. India extended an olive branch and

thigs were at peace. Former Prime Minister Vajpayee visited Lahore by bus, and

former Pakistani President Pervez Musharraf visited his birthplace in Delhi as

well. But later, Pakistan encroached upon Kargil, leading to a war between the

two countries.

This conflict occurred between May and July 1999 in the Kargil district of

Kashmir. Pakistani soldiers and militants infiltrated Indian territory, capturing

strategic positions. The Indian Army launched operations to reclaim these areas,

eventually succeeding. The war resulted in significant casualties on both sides

and heightened tensions between the nations.

War is not just a fight; it has its own stakeholders. Like in business, there are

vested interests. The real benefits of a war often go to those behind the scenes.

Historically, when kings fought, it was to conquer territories or for personal

gains.

In 1497, King Manuel I of Portugal sent Vasco da Gama to find a sea route to

India, aiming to access the lucrative spice trade. Da Gama’s arrival in Calicut in

1498 marked the beginning of European colonial interests in India.

Likewise, the British came to India primarily for trade but eventually took

control of vast territories. Their rule led to significant economic exploitation,

often referred to as the “drain of wealth,” where resources and wealth were

transferred from India to Britain.

Even during ancient dynasties, wars had profound impacts. The war, Kalinga

was one of the scariest. Fought around 261 BCE between Emperor Ashoka of

the Mauryan Empire and the state of Kalinga (present-day Odisha), this war was

one of the deadliest in Indian history. The massive bloodshed and suffering led

Ashoka to embrace Buddhism and adopt non-violence, marking a significant

shift in his reign.

When discussing the stakeholders of war, we must consider who benefits. The

weapon industry is one of the largest globally. Without conflicts, the demand for

weapons diminishes.

Let’s take a closer look at how much these nations allocate from their GDP

towards defence spending:

India spends approximately 1.91% of its GDP on defence (as of 2024-25), with

continued emphasis on self-reliance through the ‘Aatmanirbhar Bharat’

initiative.

Pakistan allocates around 3.7% of its GDP, which is one of the highest in the

region, despite its struggling economy.

China spends about 1.7% of GDP on its defence budget, though in absolute

terms, it ranks second globally due to its massive economy.

United States allocates roughly 3.4% of its GDP, maintaining the largest defence

budget in the world.

Israel witnessed a sharp surge in 2024, with a 65% increase in defense spending

due to ongoing regional conflicts.

Leaders and generals advocating for wars are often not on the front lines. Their

focus is on the economic gains from the defence industry. Corruption in defence

deals is not uncommon.

Bofors Scandal in 1980s is one of the best examples. In the 1980s, allegations surfaced that Swedish arms manufacturer Bofors paid kickbacks to Indian polititians and defence officials to secure a contract. This scandal significantly impacted the Indian political landscape and contributed to the fall of Rajiv Gandhi’s government. Between 2000 and 2023, over 1,800 corruption cases were reported in the

Indian Armed Forces, highlighting systemic issues in defence procurement and

operations.

In modern economies, war can be seen as a necessity for those in power. It

sustains a parallel economy. For instance, the U.S. invasion of Iraq was

officially about eliminating weapons of mass destruction.

While the stated reason was to dismantle Iraq’s alleged weapons of mass

destruction, many analysts believe controlling Iraq’s vast oil reserves was a

significant motive. Post-invasion, U.S. companies secured major oil contracts,

and the country’s oil infrastructure underwent significant changes.

Currently, there’s open conflict on our borders. Our economy is weak, and

Pakistan’s situation is even more dire. Both countries face severe environmental

challenges, extreme heatwaves, frequent floods, and failing crops. Yet, war

remains a visible narrative, or perhaps someone wants us to see it that way.

There’s a proverb to recall: “To mask something that happens in the house, we can set fire to the fields.”